A minha esposa partilhou este vídeo e mais 8 (!) da mesma pessoa. Tem uma voz muito “asmr” e escolhe poemas incríveis. É um jovem que ama poesia e que valoriza a literacia em geral. Já publicou um livro das suas próprias obras. Os seus vídeos até têm legendas! Recomendo como boa opção para quem quiser descobrir a poesia portuguesa.

Tag: poesia

Crónica: Tradução

I’m having trouble focusing on this poem, which I mentioned in yesterday’s post about Pedro and Inês, and holding it in my head while translating, long enough to take it all in so I’m going to write out a translation of the five pages I have in English. I can’t find a version of it online other than this which only really allows you to see a tiny piece at a time so if you want the original you’ll need to buy it like a decent upstanding citizen.

CAPÍTULO XXVII

COMO ELREI DOM PEDRO DE PURTUGAL DISSE POR DONA ENES QUE FORA SUA MOLHER REÇEBIDA E DA MANEIRA QUE ELLO TEVE

How I predicted the night. How many times.

How many times I rested on the deep darkness

Or your sleep only noticing one or another small sound

By night I search for your earthly now

That tiny god-space* like those ships ate deserted

Like everything is strange to anything that lives. Under the night here

I enclose the secret of these rites,

Taking apart this, my bodily landscape

Feeding an ancient glow

Hair I understood. I say nothing, this time must be valued

Little by little I renounce the sun

For the water of your eyes

I have to wait so long. This death happens slowly

I have no hunger, thirst or desire

I just come back by another road

These ships are ours

The little greyhound that sits here

Was the one that was born out of the cold we learned about

Tonight I lost myself in your fingers

I repeated your steps walking not

as fast as you wanted

that before the sunrise we would say it

See how the landscape changes. I don’t even find despair

and how many times I say I don’t have anyone here

Only this ship, undoubtedly the most beautiful

To show you.

Apparently nothing changed but in truth everything changed

A wind passed me by like the wake

of gulls on the surface of the sea

These stones in place, these arches covered in limes

Your absence drawn by a stone

Walking toward me

I don’t remember any more

My memory has swept itself clean of your face under the work of hands

And however many times I say

You can’t bear alteration

It’s late. The moon is dying. I let myself sleep.

COMO ELREI DOM PEDRO DE PURTUGAL DISSE POR DONA ENES QUE FORA SUA MOLHER REÇEBIDA E DA MANEIRA QUE ELLO TEVE

The day on which the arrival of summer was announced

The month of June, I tried to hear, drom the valley

The singing and the shouts that say the arrival of the traveller

By words of the present

Maybe I won’t find you again while this body

Stays until the time of your death

There won’t be movement. How will I be able? If

I have to separate destruction in myself

You will have to set out to find me. By the road and in the course of centuries

Those who will come to life, what part of them will come to be the same,

We are alone. Without a third person let alone more

While the night is what we alone open – that

By night you wait, seeming like earth, the earth itself in the nighttime still

Over time I will bring as much as you need. A long time ago

Chance had no part in our meeting, searching for the

Most distant, the thing that grows. It’s what I want to tell you

Far from trying at each step the beginning or the reliable piety

For sustenance over the years. The lack of response will never

Cease to pursue me. Reply to me.

We feel the pain, the knowledge the causes the forms

The things break like everything and what remains stands out

The difference, the meaning among the innovation

The inception in the act and in the wanting. The wise

finality of existence.

The end is to know you. Nothing else. I see you watching me

Even in the mirror of the sword blades, eroded

By rust, by so much

The sun still hasn’t set

There are men who think a lot. I don’t know if they bring a joyful heart to their work with the stone. They greet us and offer consultations. Nobody contradicts them. They don’t have the one thing I need to win: Your praise.

Nothing erases it from my memory. Because

I imitated the acts. I bring them with me. I guard them.

It’s a small thing.

Please, repeat with me the song:

The eyes are light

And anyone who stares into them

Has the rain, the sun,

That he requires

The current emphasises

the green, the green of your eyes.

* “esse mínimo espaço deus” – sounds like it should mean something but I’m not sure what! Deus isn’t capitalised so I am taking it as him meaning the space has some sort of godlike power, rather than it being some sort of space for God

Oof. I probably could have written a lot more footnotes for that one because there are lots of lines that make little sense to me.

Pedro e Inês

Notes jotted down from part of the Portuguese Culture Unit I am studying.

Um Resumo Simplório da História de Pedro e Inês

Pedro I de Portugal (1320-1367), antes da sua ascendência ao trono, casou com Constança Manuel, mas foi abertamente infiel com a aia dela, a galega Inês de Castro. O pai de Pedro, o então rei Afonso IV, reprovou a relação, até após a morte de Constança quando Pedro e Inês viviam com se fossem casados. Em 1355 o rei mandou o assassinato de Inês, temendo a influência da família Castro. Este ato provocou uma rebelião contra o rei por Pedro, os Irmãos de Inês e vários aliados, mas não foi bem sucedido e os dois lados na guerra concluíram um paz desassossegado. Dois anos depois, com o morte do soberano, Pedro foi aclamado rei do país e pós em andamento a sua vingança contra os homens que executaram as ordens de Dom Afonso. Logo depois, afirmou que tinha casado com Inês antes da morte dela e declarou-a como rainha. Até se diz que o cadáver de Inês foi desterrado e coroado e que os nobres foram forçado, sob pena de morte a beijar a mão dela. Seja como for, os túmulos dos amantes ficam no Mosteiro de Alcobaça, lado a lado para que, no dia da ressurreição, acordado dos seus sonos, Pedro e Inês se vejam sem demora.

As Trovas à Morte de Inês de Castro

Segundo o site Mitologia.pt , existe um poema secreta, atribuída ao então infante Pedro, mas a sua autoria é discutível. Porém, segundo o mesmo site, o comprovadamente mais antigo poema (tirando esse duvidoso) é “Trovas à Morte de Inês de Castro” de Garcia de Resende (1470-1536).

O poema é contado do ponto de vista de Inês, na hora da sua morte. Ela não culpa o rei mas sim os cavaleiros que acabaram executados por Pedro. Este decisão é interessante. Às vezes, vemos obras de arte que evitam responsabilizar uma figura histórica porque a figura anda favorecida pelo povo ou pelas autoridades atuais. Será que o rei da sua época desfavoreceria qualquer pessoa que criticou o seu antecessor? Parece-me pouco provável uma vez que um século tinha passado entre o morte do Pedro e o nascimento do poeta, mas quem sabe?

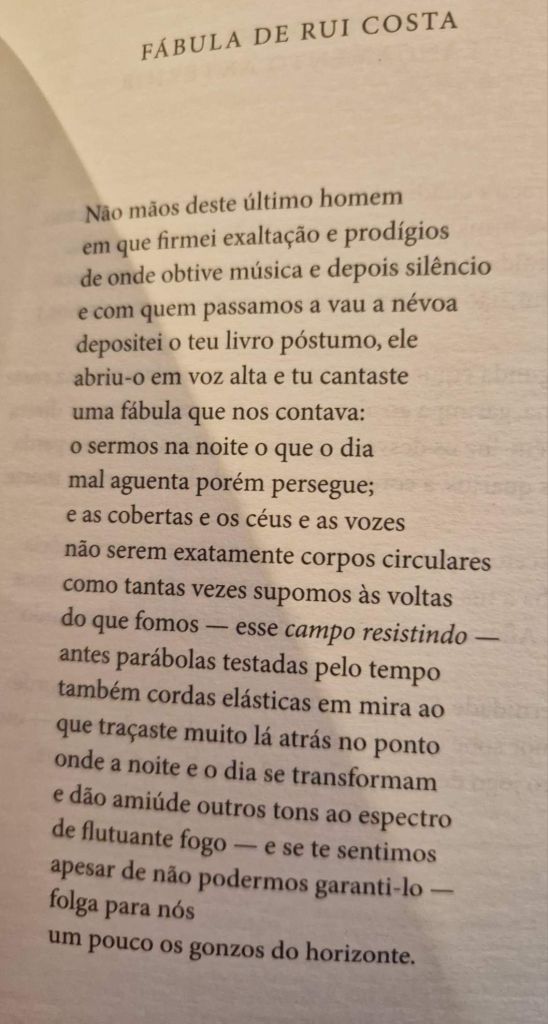

Crónica

Mais um poeta que escreveu poesia sobre a lenda é João Miguel Fernando Jorge (1943-hoje). O professor do curso forneceu-me com fotos de 7 páginas do livro “Crónica“. O que mais me marcou foi a diferença entre as primeiras linhas de cada página (por exemplo “COMO ELREI DOM PEDRO DE PURTUGAL DISSE POR DONA ENES QUE FORA SUA MOLHER REÇEBIDA E DA MANEIRA QUE ELLO TEVE” e o resto do texto que é escrito em português moderno. A razão custou-me descortinar: A obra do Jorge é uma espécie de atualização ou de recontagem de uma obra mais antiga, especificamente a “Crónica de Don Pedro I°” de Fernão Lopes (1418-1459) o escrivão e cronista do reino de Portugal, daí a sua ortografia antiga.

Teorema

Teorema é um conto de Herberto Helder. Helder (1930-2015) foi um poeta madeirense, mas, ao que parece, também soube escrever prosa. E sendo ele madeirense, por acaso, não tive de ler o conto online porque a madeirense que tenho em casa tem um exemplar do seu livro “Os Passos em Volta” no estante. É brutal! Adorei! É contado na primeira pessoa por Pêro Coelho, um dos dois executados por Pedro por ter participado no assassínio de Inês de Castro. Fiquei muito orgulhoso logo na primeira página porque o narrador descreve uma janela “no estilo manuelino” e eu soube instantaneamente que era um anacronismo: o estilo manuelino foi desenvolvido na época de D, Manuel I, cem anos depois da morte de D. Pedro. Mas mais tarde o narrador ouve a buzina de um automóvel e eu entendi que o conto é surrealista. A estátua do Marques de Sá da Bandeira? Mais um anacronismo, não é? E o protagonista continua com a narração enquanto o soberano come o coração dele, cru e cheio de sangue, o que não é normal. Eh pá cinco páginas esmagadoras!

Pedro Lembrando Inês

Já li dois livros de Nuno Júdice (1949-2024), mas não sabia que ele também escreveu um poema do ponto de vista de Pedro, nos anos após a morte da sua amante

O Guardador de Rebanhos – Alberto Caeiro

Tendo lido um excerto deste conjunto de poemas de Alberto Caeiro (um dos Heterónimos de Fernando Pessoa), decidi ler o resto, para acompanhar uma das minhas sessões de fazer um puzzle e ouvir audiolivros. Existe uma versão no youtube que é ótima, mas não pago pelo serviço sem anúncios e… ora bem, basta dizer que a poesia soa melhor sem anúncios…

Os poemas descrevem a sua vida solitária, a escrever poesia para estar sozinho, e a cuidar os seus pensamentos como se fosse um pastor a guardar um rebanho no campo. A filosofia deste poeta está em sintonia com a ruralidade no seu redor: “penso com os olhos e com os ouvidos / E com as mãos e os pés” e sente-se maior quando vê um céu aberto do que quando está numa cidade, rodeado por prédios. Um poema que me marcou é o número XX que compara o Tejo com o rio que corre pela sua aldeia. Ainda que o Tejo seja belo, é mais famoso, ou seja, mais público, e quando as pessoas o veem, pensam na sua história e no seu percurso da Espanha para o Atlântico e daí em direção à America. Mas o seu rio é o seu rio e mais nada, e “quem está ao pé dele está só ao pé dele”.

Acabei por ouvir três vezes, e acho que a gravação do poema seria um excelente acompanhamento para um passeio ou uma hora de jardinagem

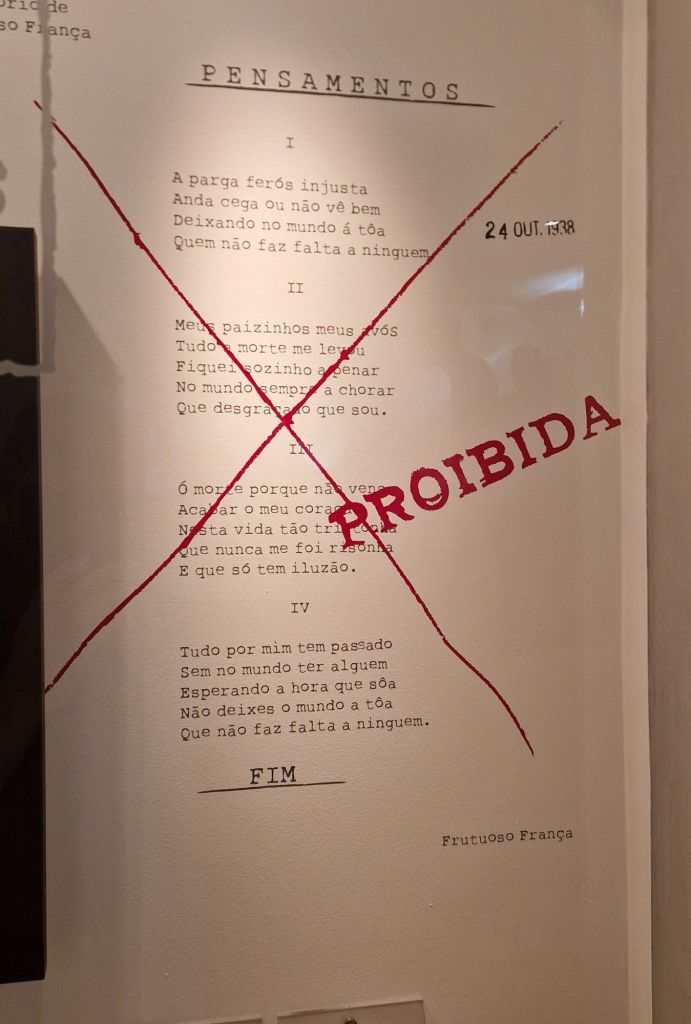

Proibida

Following on from the last post – this picture I took at the Museu do Fado contains Fazer falta, and it’s prohibited so I am drawn to translate it…. Pre-AO spelling though so ironically it’s just as illegal now as it was then 🙂

The fierce, unjust heap

Is blind or doesn't see well

Randomly leaving in the world

People who won't be missed

My parents, my grandparents

Death has taken everyone from me

I was left alone, suffering

In the world, always crying

What an outcast I am

Oh death, why don't you come for me

To stop by heart

In this sad life

That was never cheerful for me

And only has illusion

Everything is over for me

Without having anyone in the world

Weighting for the hour that sounds

Don't leave the world at random

That nobody will miss

It’s interesting isn’t it? First of all, that first word, parga, is quite unusual. It’s a heap of stored hay and grain stored away from the weather (silage?). I wonder if it had some other meaning on the 1930s. Alternatively, it might even be a typo, because praga (plague) would make a lot of sense.

I’m also interested in the slight shift in wording between the last two lines of the first verse and the last two of the last. I wonder what difference it makes. I feel like there’s a shift in emphasis there but I can’t quite put my finger on it.

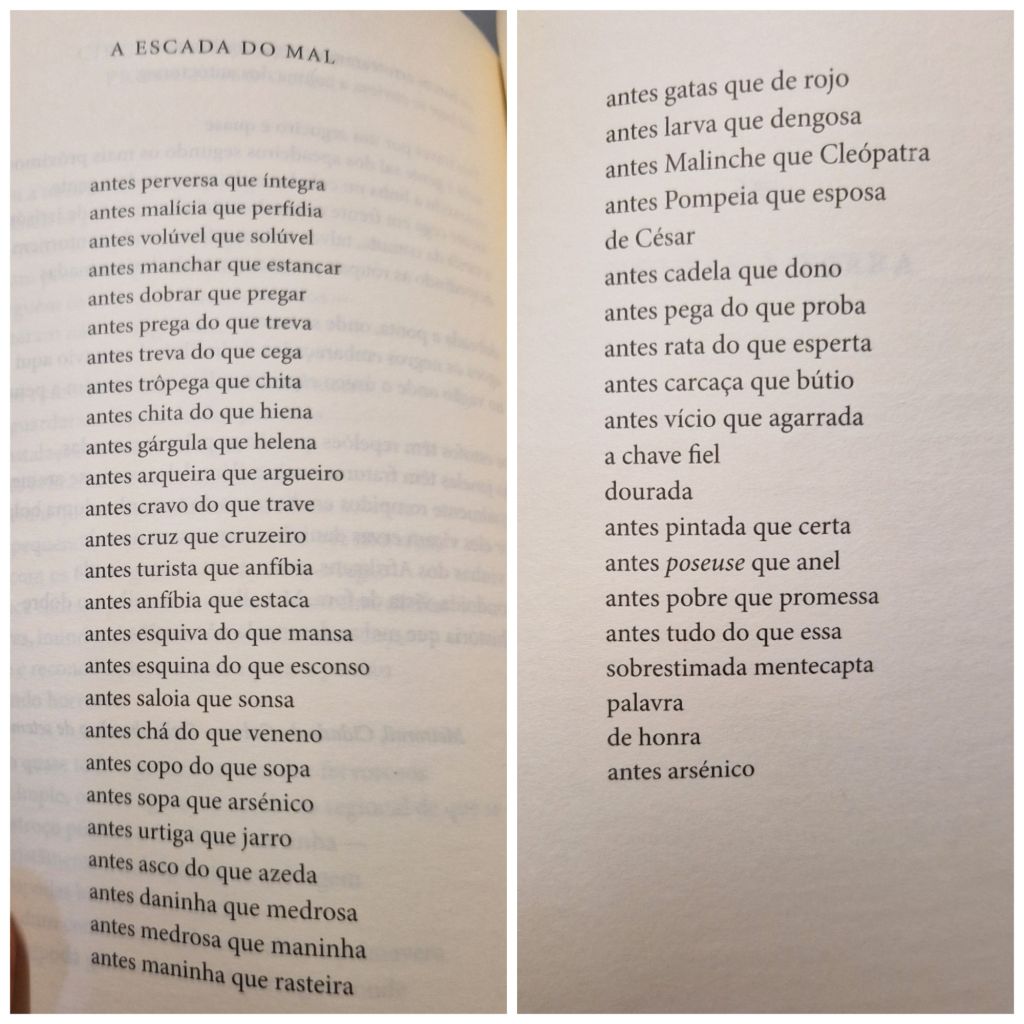

A Escada do Mal

Someone or other once said that poetry isn’t a puzzle to be solved, but it annoys me to see someone clearly doing something clever and I don’t understand it so I thought I’d dig into this one and see what was going on. It’s from Atirar Para o Torto.

OK, let’s do this….

Most of the lines are in the form Antes ……….. (do) que ……. Which in english would be something like “Better a ………. than a ……..” or “I’d rather …………. than ………..” or “I’d prefer ……. to ……”.

Some lines use “do que” and some just “que” on it own, so i have one eye on this page which I usually use as a reference when I’m not sure which to use, and I’m curious to see how closely the poem follows the strict rules. Not very, I expect. Actually, not at all. If you look at the pattern, the presence or absence of the “do” depends on the number of syllables. Que sounds better with longer words, Do Que with shorter

Quite a lot of the words have multiple meanings so part of the game is working out which meaning the writer intends. In some cases the resulting sentence sounds ridiculous and I am pretty sure I have the wrong end of a few sticks, but for what it’s worth, here’s my best shot….

A ESCADA DO MAL

antes perversa que íntegra – better perverse than entire

antes malícia que perfídia – better malice than perfidy

antes volúvel que solúvel – better voluble than soluble

antes manchar que estancar – better to stain than to staunch

antes dobrar que pregar – better to fold than to pin

antes prega do que treva – better a fold than darkness

antes treva do que cega – better darkness than blind

antes trôpega que chita – better immobile than linen (um…. don’t get this one!)

antes chita do que hiena – better cheetah than hyena (second meaning of chita!)

antes gárgula que helena – better gargoyle than a hellenic

antes arqueira que argueiro – better a bowmaker than a speck

antes cravo do que trave – better a nail than a crossbar (assuming cravo is nail here, not a carnation)

antes cruz que cruzeiro – better a cross than a cruise

antes turista que anfíbia – better tourist than amphibian

antes anfíbia que estática – better amphibian than static

antes esquiva do que mansa – better a loner than domesticated

antes autista que sápida – better autistic than tasty

antes esquina do que esconso – better corner than garret

antes saloia que sonsa – better yokel than poser

antes chá do que veneno – better tea than poison

antes copo do que sopa – better a glass than soup

antes sopa que arsénico – better soup than arsenic

antes verbena que urtiga – better verbena than nettle

antes agreste que azeda – better bitter than sour

antes daninha que medrosa – better harmful than fearful

antes medrosa que maninha – better fearful than a little sister

antes maninha que rasteira – better a little sister than servile

antes gatas que de rojo – better on hands and knees than dragging

antes larva que dengosa – better maggot than brown-noser (dengoso has a lot of meanings – it could be a person with dengue fever!)

antes Malinche que Cleópatra – better Malinche than Cleopatra

antes Pompeia que esposa de César – better Pompey than Caesar’s wife

antes cadela que dono – better bitch than master

antes pega do que proba – better thief than honest person

antes rata do que esperta – better eccentric than astute

antes carcaça que bútio – better skeleton than lazybones

antes vício que agarrada – better addicted than hooked

a chave fiel – the faithful key

dourada – golden

antes pintada que certa – better painted than true

antes poseuse que anel – better poser than ring (than married?)

antes pobre que promessa – better poor than promise

antes tudo do que essa – better anything than that

sobrestimada mentecapta – overestimated brainless

palavra – word

de honra – of honour

antes arsénico – better arsenic.

And if you’re interested, here’s what Deepl has to say about it

rather perverse than upright

rather malice than perfidy

rather fickle than soluble

rather stain than stop

rather bend than preach

rather preach than darkness

rather darkness than blindness

rather stumble than cheetah

rather cheetah than hyena

before gargoyle than helena

before an archer

better carnation than beam

rather cross than cruise

before tourist than amphibian

rather amphibian than static

rather dodgy than meek

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)

When is a Mistake not a Mistake?

Like Alexander Fleming failing to keep his room tidy, William Webb Ellis getting away with handball or Christopher Columbus getting lost on the way to Japan, sometimes we fuck up, but the result turns out to be a kind of victory. Apparently I did this in yesterday’s post. I referred to Salena Godden as a “poetesa” thinking it was the feminine form of poet. It isn’t.

But it doesn’t matter. Why? Well, as you probably already know, poeta just means poet, and is masculine by default despite the -a ending. The equivalent of poetess is poetisa. In English almost nobody says poetess and it sounds a bit antiquated because we’re moving to a world where a job is a job and doesn’t need to change with the gender of the person performing it. Portuguese is a more gendered language generally, and if pens, TVs and hats can have gender, maybe it seems less obvious why gender has to be eliminated in words that refer to people. As a result, poetisa persists and is still used. But even though it is less of an endangered species that poetess is, don’t be surprised if you meet a poetisa who describes herself as uma poeta because why not?

But why is poetesa not a mistake then? I was baffled when I was told it actually sounded better than the right word, so I dug around, and I think it’s because of this. Esa is a suffix from latin which, when used as part of a feminine noun designates status and dignity. Well that’s good then. I don’t really know Salena Godden’s work but I bought a copy of her book Mrs Death Misses Death to read later and she signed it and I’m happy to have accidentally given her a respectful title!

Atirar Para o Torto – Margarida Vale do Gato

Já me queixei deste livro noutros lugares mas isso não significa que o livro não seja ótimo, só que tenho mais olhos que barriga e escolhi um livro demasiado difícil. Li-o todo mas deu água pela barba. O meu dicionário está completamente gasto. Como resultado não gostei do livro assim tanto, mas aprendi algumas coisas.

Enfim, não recomendo este livro aos meus camaradas nesta viagem linguística mas se és português, o livro tem 3.3 estrelas no Goodreads e os leitores que o classificaram por lá terão opiniões mais úteis do que a minha!

Am I hallucinating?

Talvez tenha estado aqui a fitar este maldito livro durante tempo demais mas… A primeira palavra deste poema é um erro topográfica, não é?

This Book Is Really Kicking My Bum

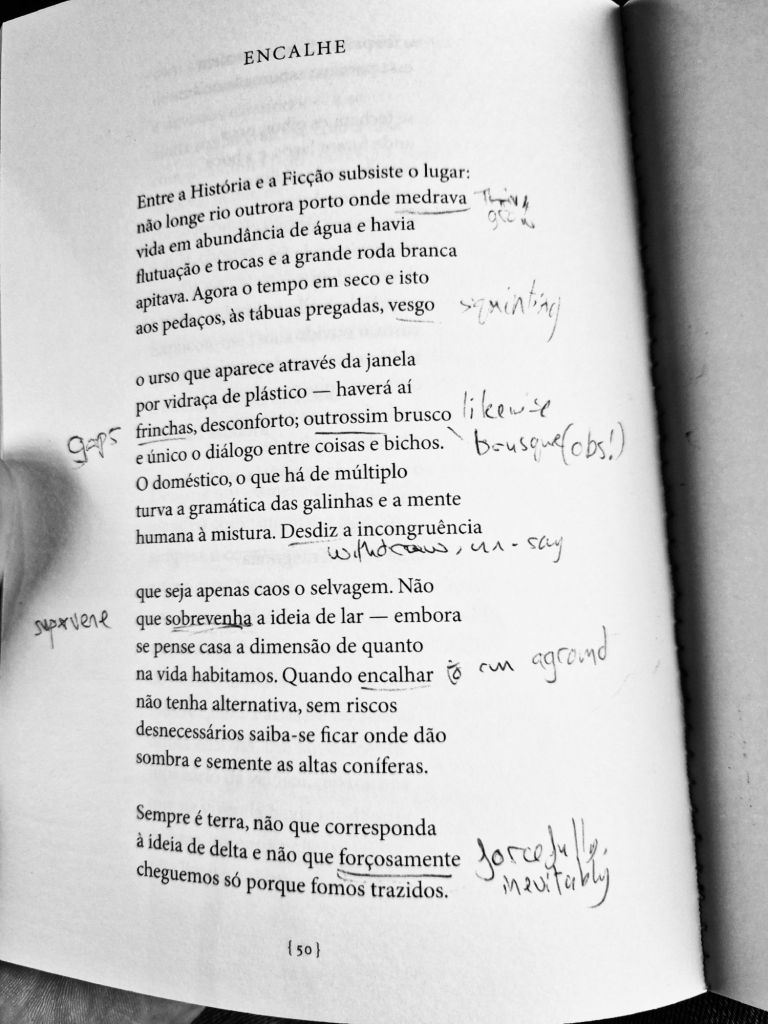

It’s Atirar Para o Torto by Margarida Vale de Gato. Just about every page brings me a whole crop of obscure vocabulary. It makes it hard to get absorbed in the flow. I underlined the mysterious strangers on this page because there were so many I couldn’t keep track. Some are obvious (“forçosamente”,”desdiz”), others I’d seen before but couldn’t remember (“frincha”) and others are total mysteries (“vesgo”). Outrossim looks like it’s combining ‘outro’ and ‘assim’ but it’s “likewise” (another one like that) rather than what I thought at first: “otherwise” (like something else entirely)

Even the title of the book was a mystery: “Atirar para o torto”. Torto can mean someone who has a physical deformity of some sort – they’re lame or cross-eyed – as in Que Mulher é Essa by A Garota Não, so I wondered in a vague way if she was taking about some sort of persecution of disadvantaged people. That wouldn’t be a great title for a poetry book though. “Para o torto” means something like “wide of the mark”, so if you threw something at me but your aim was way off, you could say you had thrown “para o torto”. So the book means something like “Shooting and Missing”.

Edit – I’ve been re-listening to old episodes of Say It In Portuguese and the word Torto comes up in this episode, so if you want to know more, have a listen.