I know everyone’s attention span is super-short these days, so here’s a TL;DR summary of all the Pedro e Inês content so far.

I know everyone’s attention span is super-short these days, so here’s a TL;DR summary of all the Pedro e Inês content so far.

Notes jotted down from part of the Portuguese Culture Unit I am studying.

Pedro I de Portugal (1320-1367), antes da sua ascendência ao trono, casou com Constança Manuel, mas foi abertamente infiel com a aia dela, a galega Inês de Castro. O pai de Pedro, o então rei Afonso IV, reprovou a relação, até após a morte de Constança quando Pedro e Inês viviam com se fossem casados. Em 1355 o rei mandou o assassinato de Inês, temendo a influência da família Castro. Este ato provocou uma rebelião contra o rei por Pedro, os Irmãos de Inês e vários aliados, mas não foi bem sucedido e os dois lados na guerra concluíram um paz desassossegado. Dois anos depois, com o morte do soberano, Pedro foi aclamado rei do país e pós em andamento a sua vingança contra os homens que executaram as ordens de Dom Afonso. Logo depois, afirmou que tinha casado com Inês antes da morte dela e declarou-a como rainha. Até se diz que o cadáver de Inês foi desterrado e coroado e que os nobres foram forçado, sob pena de morte a beijar a mão dela. Seja como for, os túmulos dos amantes ficam no Mosteiro de Alcobaça, lado a lado para que, no dia da ressurreição, acordado dos seus sonos, Pedro e Inês se vejam sem demora.

Segundo o site Mitologia.pt , existe um poema secreta, atribuída ao então infante Pedro, mas a sua autoria é discutível. Porém, segundo o mesmo site, o comprovadamente mais antigo poema (tirando esse duvidoso) é “Trovas à Morte de Inês de Castro” de Garcia de Resende (1470-1536).

O poema é contado do ponto de vista de Inês, na hora da sua morte. Ela não culpa o rei mas sim os cavaleiros que acabaram executados por Pedro. Este decisão é interessante. Às vezes, vemos obras de arte que evitam responsabilizar uma figura histórica porque a figura anda favorecida pelo povo ou pelas autoridades atuais. Será que o rei da sua época desfavoreceria qualquer pessoa que criticou o seu antecessor? Parece-me pouco provável uma vez que um século tinha passado entre o morte do Pedro e o nascimento do poeta, mas quem sabe?

Mais um poeta que escreveu poesia sobre a lenda é João Miguel Fernando Jorge (1943-hoje). O professor do curso forneceu-me com fotos de 7 páginas do livro “Crónica“. O que mais me marcou foi a diferença entre as primeiras linhas de cada página (por exemplo “COMO ELREI DOM PEDRO DE PURTUGAL DISSE POR DONA ENES QUE FORA SUA MOLHER REÇEBIDA E DA MANEIRA QUE ELLO TEVE” e o resto do texto que é escrito em português moderno. A razão custou-me descortinar: A obra do Jorge é uma espécie de atualização ou de recontagem de uma obra mais antiga, especificamente a “Crónica de Don Pedro I°” de Fernão Lopes (1418-1459) o escrivão e cronista do reino de Portugal, daí a sua ortografia antiga.

Teorema é um conto de Herberto Helder. Helder (1930-2015) foi um poeta madeirense, mas, ao que parece, também soube escrever prosa. E sendo ele madeirense, por acaso, não tive de ler o conto online porque a madeirense que tenho em casa tem um exemplar do seu livro “Os Passos em Volta” no estante. É brutal! Adorei! É contado na primeira pessoa por Pêro Coelho, um dos dois executados por Pedro por ter participado no assassínio de Inês de Castro. Fiquei muito orgulhoso logo na primeira página porque o narrador descreve uma janela “no estilo manuelino” e eu soube instantaneamente que era um anacronismo: o estilo manuelino foi desenvolvido na época de D, Manuel I, cem anos depois da morte de D. Pedro. Mas mais tarde o narrador ouve a buzina de um automóvel e eu entendi que o conto é surrealista. A estátua do Marques de Sá da Bandeira? Mais um anacronismo, não é? E o protagonista continua com a narração enquanto o soberano come o coração dele, cru e cheio de sangue, o que não é normal. Eh pá cinco páginas esmagadoras!

Já li dois livros de Nuno Júdice (1949-2024), mas não sabia que ele também escreveu um poema do ponto de vista de Pedro, nos anos após a morte da sua amante

Ouvi falar do Quinto Império há muito tempo numa conversa com uma estudante de português que conheci no Insta, mas não pensei mais nele até recentemente quando traduzi o “A Vida na Estrada” dos Diabo na Cruz que se refere à ideia. Ainda mais recentemente, o nome de Padre António Vieira, (autor do Sermão de Santo António aos Peixes) surgiu numa aula, e aquele clérigo foi o divulgador principal do Império, portanto decidi resgatar este texto da pasta de rascunhos onde jaz desde 2022!

Mas afinal, o que é o tal Quinto Império? Eis um Resumo da página de Wikipédia:

O Quinto Império é uma crença milenarista que fazia parte da mitologia do país durante a expansão do seu império ultramarino, e emprestou legitimidade e apoio religioso a esta fase de conquista. Foi construído a partir de textos anteriores, principalmente o mito das três idades promulgado pelo monge Joaquim de Flora e teve como origem o livro do Daniel, onde aquele profeta viu uma estátua com pés de barro e, apesar de ser composta de várias metais, os pés eram vulneráveis a uma pedra atirada por um inimigo. Segundo o Padre, cada parte da estátua representa um império do mundo antigo e o Império Português seria a pedra que derrubaria tudo, sendo o quinto e último império que duraria durante mil anos, estabelecendo a paz por todo o mundo e realizando a vontade de Deus.

É quase indispensável para um novo reino expansionista ter uma ideologia forte para motivar os seus funcionários e soldados

Os três pilares do movimento são os seguintes

Este mito persistiu e serviu como pano de fundo d’A Mensagem, uma coletânea de poemas da autoria de Fernando Pessoa. Já li estes poemas sem preparação mas acho que é um livro que precisa de mais conhecimento do contexto histórico e cultural.

*Sou burro, eu sei, mas este nome “ourique” lembra-me da palavra ouriço, portanto imagino esta batalha como um exército de porcos-espinhos a lutar contra os mouros para a glória de Portugal e um grande cozido de minhocas e besouros.

Lazy Post, reviewing an audiobook I finished recently, about the Lisbon Earthquake.

As the name suggests, the book is organised around the event that literally shook Lisbon and figuratively shook its empire in the middle of the eighteenth century. The day itself is described well, albeit undramatically, and the Marquês de Pombal’s life and legacy gets laid out, including the grizzly bits. Smashing people’s arms and legs with hammers, burning them alive. Oh, and rebuilding the city in line with modern techniques. He’s… Well, to borrow another term from the young folk, “morally grey”.

Anyway, so far so good, but it could have been more focused. I guess his thinking was that a lot of readers wouldn’t know the background so he gives us a tour of the main points of Portuguese history but he doesn’t section it off, he just sort of rambles back in the middle of the book. Maybe the general history stuff would have been better as an optional preamble to the main book. That way, he could have really drilled down both in the horror and chaos of the day itself and on the technical details of how they recovered. I want details, dammit!

My favourite aspect was his summary of how the different groups explained the event. We sometimes think our age is uniquely divided and that the two sides in our political disputes operate with different worldviews and different sets of facts, but in 1755 we have catholics fulminating about how God sent the earthquake for allowing the protestant heretics into Portugal and meanwhile in England, at memorials services for lost Port wine merchants, the vicars are telling their flocks it’s no wonder Portugal was ruined when it is full of dreadful popish idolatry.

Some things never change.

The audiobook reader gets a solid 8/10 for trying with the pronunciation. He obviously doesn’t speak portuguese, but he’s put the effort in to learn the ground rules of portuguese pronunciation and it shows. Instead of just saying all the names like they were Mexican drug lords in Breaking Bad, he pushes in the right direction. He gets a lot wrong, but he’s tried and I appreciate that.

Já publiquei uma tradução de outra canção de Chico Buarque, mas ouvi falar desta em relação às comemorações do aniversário da Revolução dos Cravos. Hum… não me sinto grande fã deste artista, mas cada vez que escuto com mais atenção uma música dele, adoro-a e aprendo muito. Acho que chegou a hora de ouvir os seus discos todos.

(Ah ah ah, discos, sim, escute os seus discos, avô, nós estamos a ouvir no Spotify)

“Tanto Mar” é uma música que ilustra certas coisas sobre a época e sobre a relação entre os dois países, Portugal e o Brasil. Existem duas versões na Internet, e eu pensei, “está bem, a segunda é uma gravação nova da mesma canção”. Mas não é! O cantor escreveu a primeira versão em 1975, um ano depois da revolução e dedicou-a ao povo português – ou melhor, à revolução em si. Naquela altura, o Brasil também estava em plena ditadura militar (um governo que permaneceu em vigor desde 1964 até 1985), portanto a revolução no país menor deu motivo para esperança no maior. As letras refletem aquela esperança mas por isso mesmo, foram censuradas pela ditadura brasileira.

A segunda versão foi lançada 3 anos depois, em 1978, mas desta vez com letra atualizada. Existe um sentimento agridoce perante a crise de 25 de Novembro, o enfraquecimento dos objetivos da revolução e a realidade que a passagem dos anos trouxe. Mas apesar de tudo, a esperança é ainda evidente.

Em baixo, traduzi as duas versões. Gosto da simplicidade da poesia. Um escritor menos talentoso teria tentado escrever algo maior, e teria enchido cada verso de sentimentalismo e cliché, mas esta letra é curta e limpa e não tem uma única palavra a mais.

Just a reminder, obviously, this is in PT-BR, so in case anyone is avoiding brazilian accents on their learning journey, allow me to sound the 📢#BRAZILIANPORTUGUESEKLAXON📢 as a warning.

| Português | Inglês |

|---|---|

| Sei que estás em festa, pá Fico contente E enquanto estou ausente Guarda um cravo para mim | I know you’re having a party, man I’m glad And while I’m away Save a carnation for me |

| Eu queria estar na festa, pá Com a tua gente E colher pessoalmente alguma flor No teu jardim | I wanted to be at the party, man With your people And pick a flower in person in your garden |

| Sei que há léguas a nos separar Tanto mar, tanto mar Sei também quanto é preciso, pá Navegar, navegar | I know there are miles* between us So much sea, so much sea And I know how much we’d have to Navigate, navigate** |

| Lá faz primavera pá Cá estou doente Manda urgentemente Algum cheirinho de alecrim | It’s spring there, man Here, I’m sick Send, urgently, some Fleeting scent of rosemary |

| Português | Inglês |

|---|---|

| Foi bonita a festa, pá Fiquei contente Ainda guardo renitente Um velho cravo para mim | It was a great party, man It made me happy I still hold stubbornly An old carnation for myself |

| Já murcharam em tua festa, pá Mas certamente Esqueceram uma semente Em algum canto de jardim | The (flowers) withered at your party man But certainly They left a seed In some corner of the garden |

| Sei que há léguas a nos separar Tanto mar, tanto mar Sei também quanto é preciso, pá Navegar, navegar | I know there are miles* between us So much sea, so much sea And I know how much we’d have to Navigate, navigate** |

| Canta a primavera, pá Cá estou carente Manda novamente Algum cheirinho de alecrim | Sing the spring, man Here I am in need Send me again Some fleeting scent of rosemary |

* =Léguas is more like leagues but it would sound confusing in english so I fudged it

**Maybe I should have fudged this one too: naveger is much more specifically about travelling in a ship, as opposed to english where it’s more like “finding your way”

Yesterday’s post was about the strange case of Fernando Pessoa’s advertising slogan for Coca Cola in 1927. As I mentioned, there seem to be a few different perspectives on the motives of the people involved, but I don’t think the facts of the matter are in doubt.

Anyway, it turns out that there’s a short movie about the incident. It’s made by a French company but it’s in portuguese with English subtitles. Someone’s put it on Facebook. Hurry though, it might not be there forever. It’s a good length and very easy to follow, so I can recommend it even if your listening skills are underdeveloped.

The film has a slightly playful, surreal tone. The name of the drink os given as “Coca Louca” and it translates the slogan as “First you’re surprised, then you’re possessed”, then plays with that idea of possession by showing the minister for health convinced that the drink contains evil demons which need to be cast out by an exorcist with a bottle opener in the shape of a crucifix!

It also depicts the poet not as Pessoa himself but as Álvaro de Campos, one of the heteronyms, who appears in the film as a separate person, looking just like the man himself.

I can’t remember if I’ve mentioned this account in here before but it really is a great source of minor historical weirdnesses if you are a fan of Portuguese History. I mean, this for example.

I’ve got a backlog of texts I’ve written for this blog but there aren’t many correctors around so the last couple of days’ posts are still sitting in drafts. They’ll all arrive in a rush, five at a time, I expect.

OK, let’s try and decipher why this tweet is funny. I have no idea but I expect finding out will be an educational experience…

Bazar is a sort of slang way of saying “leave” and Fazer a folha a alguém means making a leaf but as an expression it means plotting against someone. So…

The Mestre de Avis getting out of Paço after scheming against Count Andeiro (1383)

Basically, the gist of the story is here, and it goes back to the interminable story of Spain (Castille) wanting to dominate Portugal. After the death of Dom Fernando I in 1383, there was a wrangle over succession. Fernando’s only daughter had already been promised in marriage to King Juan I of Castille (despite being er… Only ten years old at the time… OK, let’s try not to think about that too much) but there was a treaty in place (O Tratado de Salvaterra de Magos) that explicitly ruled out Castille claiming dominion over Portugal as a result of that alliance.

João Fernando de Andeiro, known as Conde Andeiro had been a close advisor of Dom Fernando and remained a power in the land and a powerful influence over Fernando’s wife, Dona Leonor. But he was galician, born in Spain and there were rumours that he was too friendly toward Castille and that he was sleeping with Leonor and using his leverage as a way to undermine Portuguese independence. Things came to a head when Juan turned up in Santarém “persuaded” Leonor to renounce her regency and to allow the monarchy to pass to him and his primary-school-age wife.

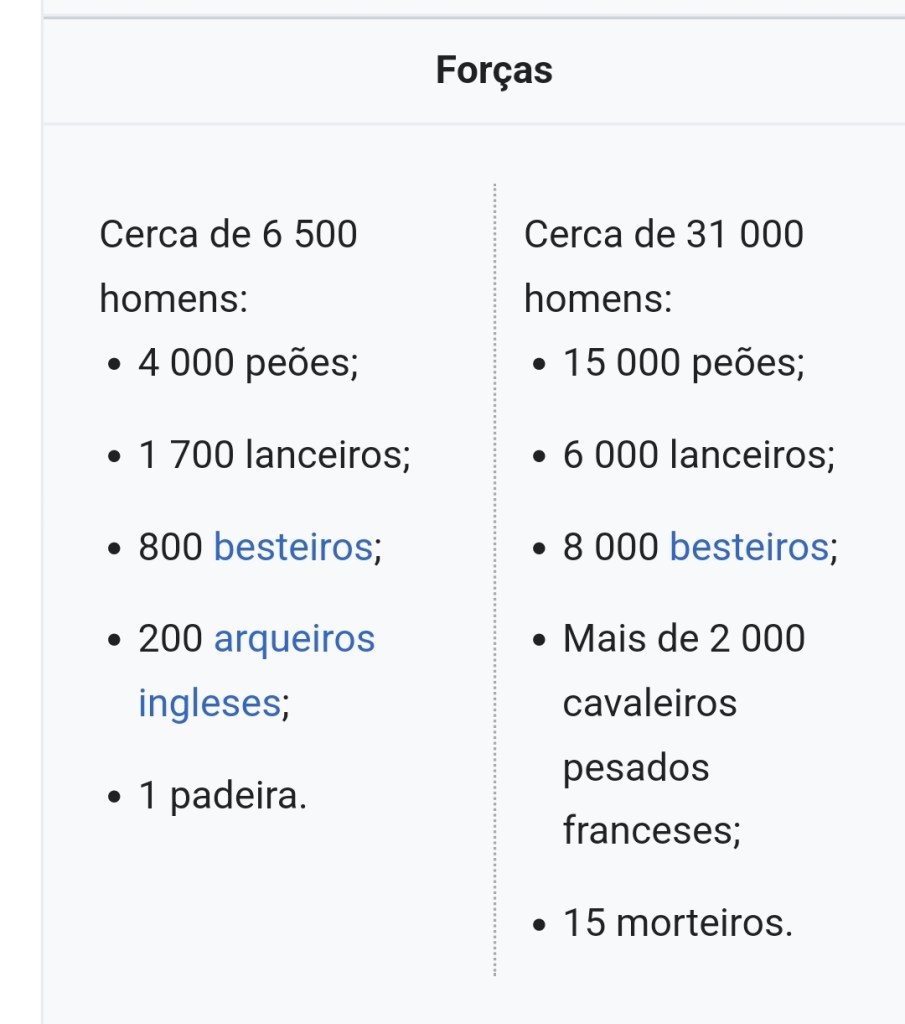

The Mestre de Avis, later known as João I, meanwhile had been proposed as an alternative successor to the throne by the court of Coimbra, and he rocked up one day in Paço with a bunch of friends and beat Andeiro to death. Thus started a crisis in the Portuguese succession which lasted a couple of years, culminating in the Battle of Aljubarrota, in which the Spaniards had their arses handed to them. Hilariously, the wiki page of the battle enumerates the forces on both sides and includes “1 padeira” on the Portuguese side. That’s a reference to A Padeira de Aljubarrota, a national hero. Her real name was Brites de Almeida and when she returned to her bakery after the battle she found seven Spaniards taking refuge in her bread oven (what? How big was the thing?) so she beat them with a shovel, slammed the door and lit the fire to bake them to death along with her bread. I have difficulty visualising this story to be honest, but I guess I’m not an expert in mediaeval bread-making technology.

Second title in a row that hasn’t had any proper words in it but I think you’ll agree it’s merited: I mentioned a while back that I have been following a “Portuguese History” course delivered by two University lecturers, at least one of whom is also a TV pundit and alleged plagiarist. The course title is a bit of a misnomer because they mostly just deliver sermons on Marxist theory using Portugal as an example, but that’s cool, I don’t mind a little light Marxism.

Anyway, today I came across this clip of her on TV “a papaguear” (brilliant verb meaning “to parrot”) Putinist propaganda. Sigh. I think I might see if I can switch to a different course. I can’t be arsed with this.

For the benefit of anyone who is too lazy to read that last post, here it is in the form of a meme. I actually posted it on a world history Facebook group and it was modded out of existence almost immediately. Not surprising I suppose but I thought there might be one or two people willing to do the work to decipher it.