One of the first things we learn in Portuguese classes is the difference between the various ways of addressing another person; that there are different second-person pronouns for strangers vs friends: Você, Tu, or you can just flip it to third person with something like “O Senhor”. But we tend to get the impression that it’s just a linguistic rule with no further importance, as if it were a puzzle to be solved or a code to be cracked.

But there are cultural differences that underlie these kinds of distinctions: language has a social meaning as well as a semantic one. English doesn’t really have the same hard-wired social distinction*: if we want to be snobbish or arrogant or condescending we have to resort to using tones of voice.

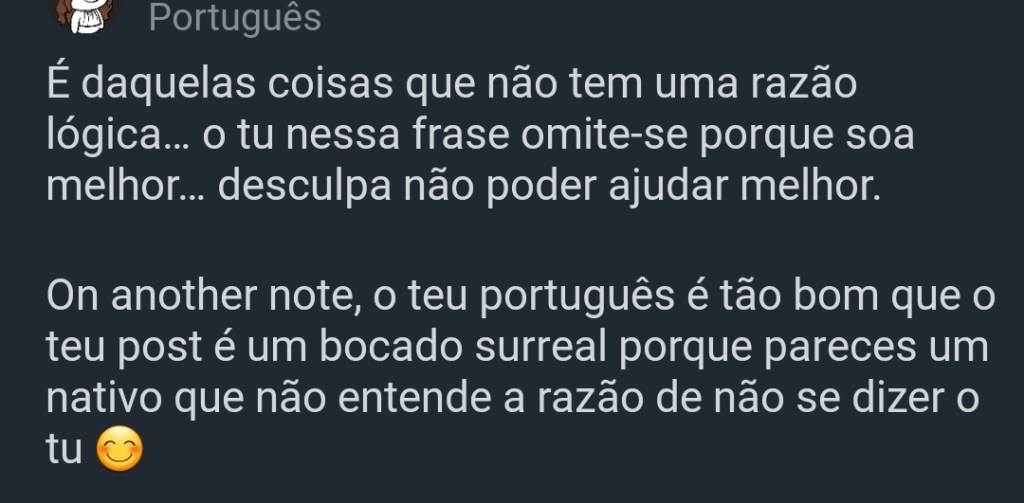

You can catch glimpses of this social distance in literature and films: people taking offence at being treated with too much or too little formality (as in the picture above, taken from Gente Remota) or asking permission to use different pronouns (which happens near the end of Os Gatos Não Têm Vertigens). And it makes me wonder to what extent this creates a barrier between people, or makes them think of themselves differently, as a result of this very clear social distance marker being applied to them by someone else.

There’s a new blog on Say It In Portuguese that aims to shed light on the cultural dimension of these kinds of interaction. Its Part 1 in a two part series, and I’m looking forward to the second part. If you’re looking to deepen your understanding of Portuguese culture, head on over and have a look.

*This was probably less true in the recent past. The title of this blog post alludes to a distinction made by Nancy Mitford in the 1950s between U and Non-U English. The satire boom of the sixties and seventies punctured that pomposity. But even then, it was much more common when I was young m to hear people addressing each other as Mr So-and-So as a mark of respect or formality. That’s getting increasingly rare. We’re all tus.