Someone or other once said that poetry isn’t a puzzle to be solved, but it annoys me to see someone clearly doing something clever and I don’t understand it so I thought I’d dig into this one and see what was going on. It’s from Atirar Para o Torto.

OK, let’s do this….

Most of the lines are in the form Antes ……….. (do) que ……. Which in english would be something like “Better a ………. than a ……..” or “I’d rather …………. than ………..” or “I’d prefer ……. to ……”.

Some lines use “do que” and some just “que” on it own, so i have one eye on this page which I usually use as a reference when I’m not sure which to use, and I’m curious to see how closely the poem follows the strict rules. Not very, I expect. Actually, not at all. If you look at the pattern, the presence or absence of the “do” depends on the number of syllables. Que sounds better with longer words, Do Que with shorter

Quite a lot of the words have multiple meanings so part of the game is working out which meaning the writer intends. In some cases the resulting sentence sounds ridiculous and I am pretty sure I have the wrong end of a few sticks, but for what it’s worth, here’s my best shot….

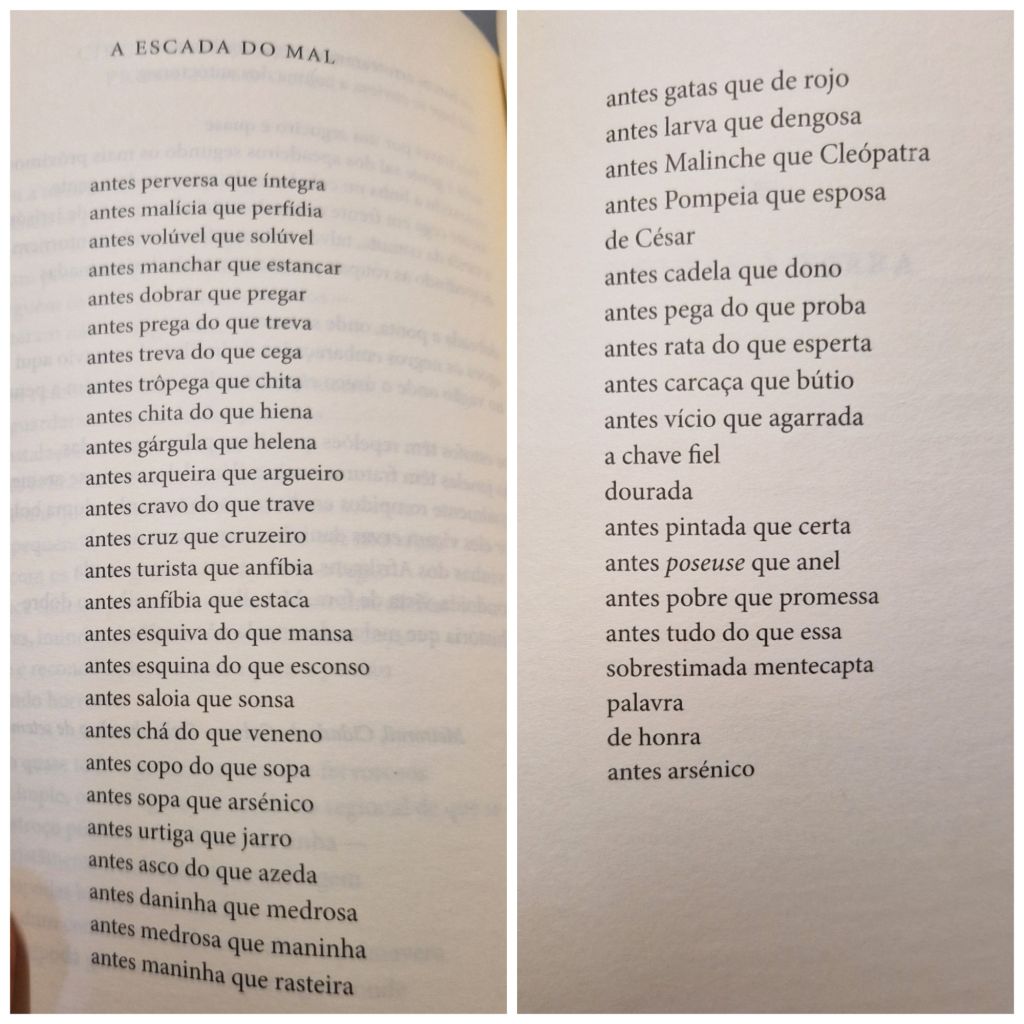

A ESCADA DO MAL

antes perversa que íntegra – better perverse than entire

antes malícia que perfídia – better malice than perfidy

antes volúvel que solúvel – better voluble than soluble

antes manchar que estancar – better to stain than to staunch

antes dobrar que pregar – better to fold than to pin

antes prega do que treva – better a fold than darkness

antes treva do que cega – better darkness than blind

antes trôpega que chita – better immobile than linen (um…. don’t get this one!)

antes chita do que hiena – better cheetah than hyena (second meaning of chita!)

antes gárgula que helena – better gargoyle than a hellenic

antes arqueira que argueiro – better a bowmaker than a speck

antes cravo do que trave – better a nail than a crossbar (assuming cravo is nail here, not a carnation)

antes cruz que cruzeiro – better a cross than a cruise

antes turista que anfíbia – better tourist than amphibian

antes anfíbia que estática – better amphibian than static

antes esquiva do que mansa – better a loner than domesticated

antes autista que sápida – better autistic than tasty

antes esquina do que esconso – better corner than garret

antes saloia que sonsa – better yokel than poser

antes chá do que veneno – better tea than poison

antes copo do que sopa – better a glass than soup

antes sopa que arsénico – better soup than arsenic

antes verbena que urtiga – better verbena than nettle

antes agreste que azeda – better bitter than sour

antes daninha que medrosa – better harmful than fearful

antes medrosa que maninha – better fearful than a little sister

antes maninha que rasteira – better a little sister than servile

antes gatas que de rojo – better on hands and knees than dragging

antes larva que dengosa – better maggot than brown-noser (dengoso has a lot of meanings – it could be a person with dengue fever!)

antes Malinche que Cleópatra – better Malinche than Cleopatra

antes Pompeia que esposa de César – better Pompey than Caesar’s wife

antes cadela que dono – better bitch than master

antes pega do que proba – better thief than honest person

antes rata do que esperta – better eccentric than astute

antes carcaça que bútio – better skeleton than lazybones

antes vício que agarrada – better addicted than hooked

a chave fiel – the faithful key

dourada – golden

antes pintada que certa – better painted than true

antes poseuse que anel – better poser than ring (than married?)

antes pobre que promessa – better poor than promise

antes tudo do que essa – better anything than that

sobrestimada mentecapta – overestimated brainless

palavra – word

de honra – of honour

antes arsénico – better arsenic.

And if you’re interested, here’s what Deepl has to say about it

rather perverse than upright

rather malice than perfidy

rather fickle than soluble

rather stain than stop

rather bend than preach

rather preach than darkness

rather darkness than blindness

rather stumble than cheetah

rather cheetah than hyena

before gargoyle than helena

before an archer

better carnation than beam

rather cross than cruise

before tourist than amphibian

rather amphibian than static

rather dodgy than meek

Translated with DeepL.com (free version)