Today I had a lesson with a Portuguese teacher via Skype. She follows me on Instagram so she asked me about a picture I’d posted of some birds that have made a home in a nesting box on our allotment. So I described them, but I hit a problem fairly early on: I don’t know the names of many birds. Let’s see… umm… corvo (crow), pomba (pigeon), farm birds like Ganso, Pato, Galinha, Peru, um… what else? Ostrich, I think is avestruz, eagle is… águia (I needed spellcheck’s help even on that one), owl is coruja (I only know this from reading Harry Potter e a Pedra Filosofal), and melro-preto I know from a song is a blackbird. That’s about it. Sadly, the nesting birds were not blackbirds, nor owls, much less ostriches, so that put paid to that. So I went to my old friend google translate to find out how to say “blue tits”. If you’re british you know blue tits and great tits are real birds whose place in the comedy double-entendre pantheon of our island nation is inestimable. But the reason the liked of Benny Hill have been able to exploit their comic potential is that “tit” also means something else.

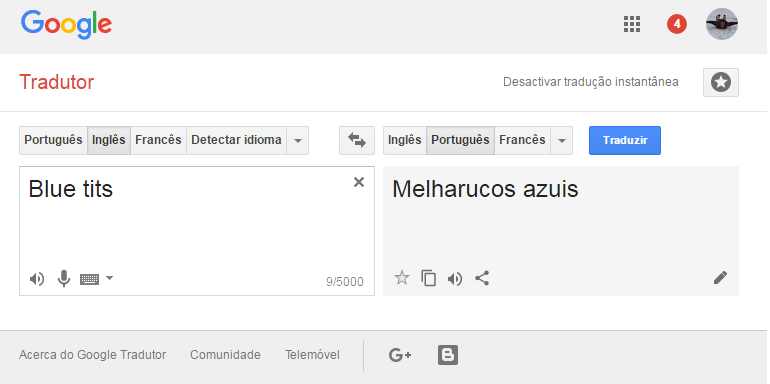

Here’s what I got:

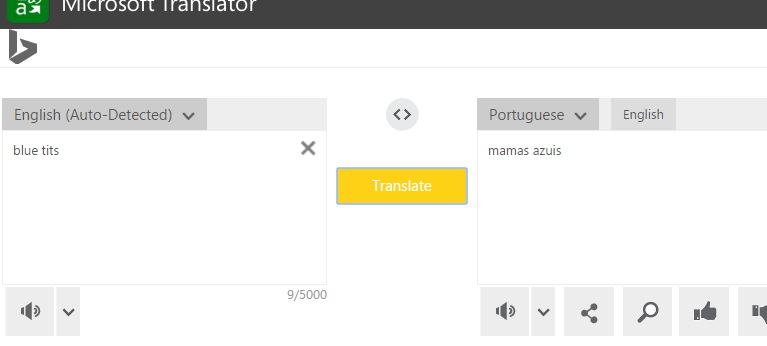

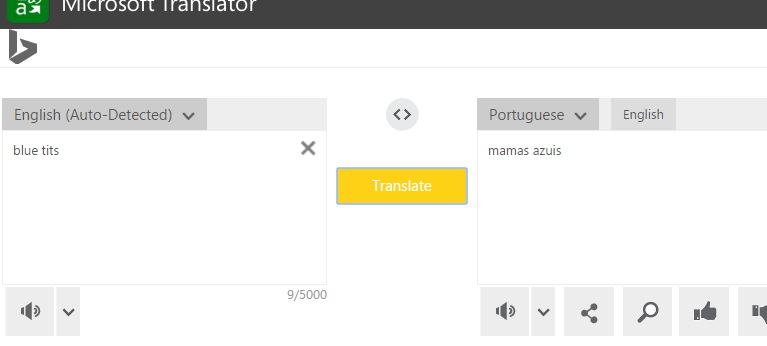

I was none the wiser. Should I just blurt it out and hope she didn’t burst out laughing? I blurted, while simultaneously plugging the words back into google search and was reassured to see lots of images of actual feathery blue tits. This is one of those times when the choice of tools matters though because if I’d used Bing Translate I would have got this…

…which actually does mean blue breasts (bit not the cruder “tetas” which is more of a direct equivalent for “tits”).

Bird names are a minefield, actually. There’s a bird called a shag and another called a booby. It’s almost as if, when Adam named all the animals, he started getting bored by the time he reached the birds and decided to see what he could get away with.

So what’s the message? Something about not letting Bill Gates teach you how to speak a language, I think.