This one is inspired by yesterday’s post in which I was initially suspicious of the loja online because it mentions Halloween, in English. Hallowe’en (“dia das bruxas”) is an old celtic tradition but its best-known manifestation, with pumpkins and vampires and slutty nurses is all American cultural hegemony. I’ve been seeing posts talking about Portuguese traditions and I thought it might be fun to talk about this one…

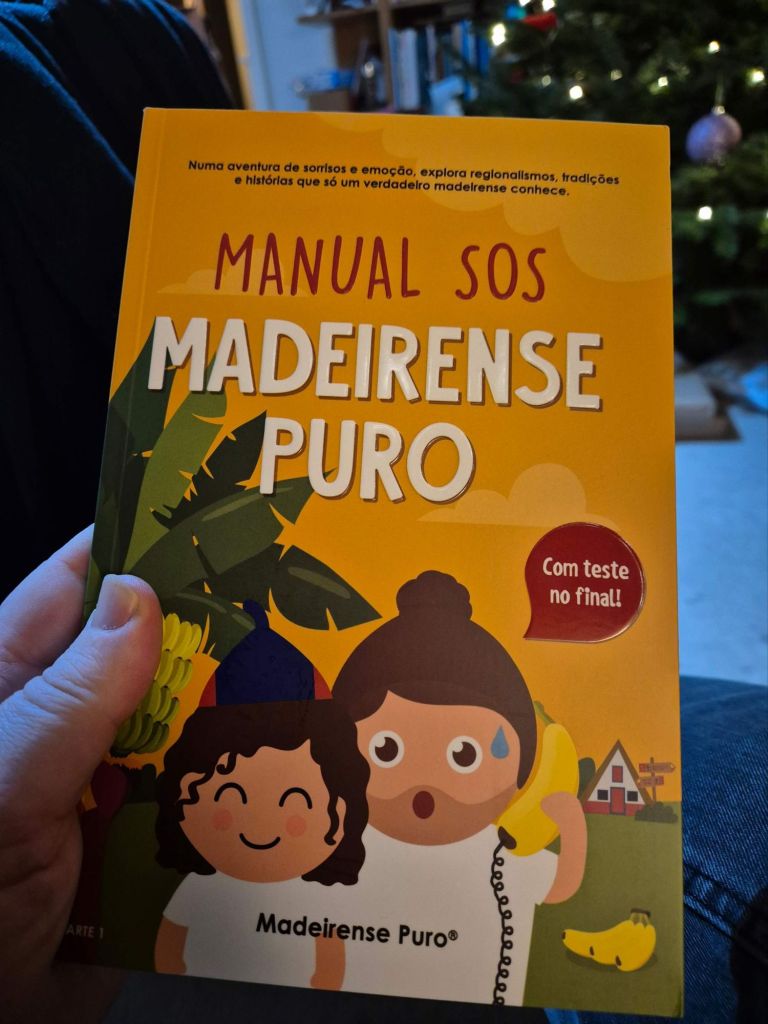

O vídeo (infra) foi feito por mais uma loja online, Madeirense Puro, que tem, como foco, outros portugueses. Já escrevi sobre o livro dele e acho que existe uma sequela mas ainda não tenho. No vídeo, os empregados fingem estar numa manifestação contra o Halloween (“abaixo as aboboras!”) e a favor do Pão Por Deus. Segundo a página da Wikipédia, Pão Por Deus é uma tradição religiosa que tem laços ao festival que domina esta estação do ano mas tem lugar no próximo dia, o dia de todos os santos e portanto coloca a ênfase no lado santo da estação em vez do lado do caos e terror!

A tradição tem raízes na noção de alimentar os defuntos e de pedir esmola em tempos de fome. Especificamente, a tradição de ir de porta em porta a pedir pão “por deus” é associada com a época do terramoto, que também aconteceu no dia de todos os santos. Hum… se não me engano, este facto piorou a situação ainda mais porque as velas acesas nas igrejas causaram incêndios, acima dos danos do terramoto em si. Mas seja como for, continua como tradição até aos dias de hoje. Contudo, como podem ver neste segundo vídeo (narrado em português brasileiro – desculpa!) a sombra dos estados unidos cai através a tradição. Vemos crianças a usar cornos do diabo, chapéus de bruxa e até fantasias de abóboras. Porém, têm também sacos decorados, e a procissão decorre durante as aulas em vez da noite, com os pais.

O Podcast preferido de todos os novatos na aprendizagem de português é o Practice Portuguese, e o Rui fez um vídeo com uma amiga sobre as tradições regionais do Pão Por Deus e o dia das bruxas. Falam também dos bolos tradicionais (receita aqui). Como sempre, falam nitidamente e num sotaque deste lado do Atlántico, que é sempre bem vindo.