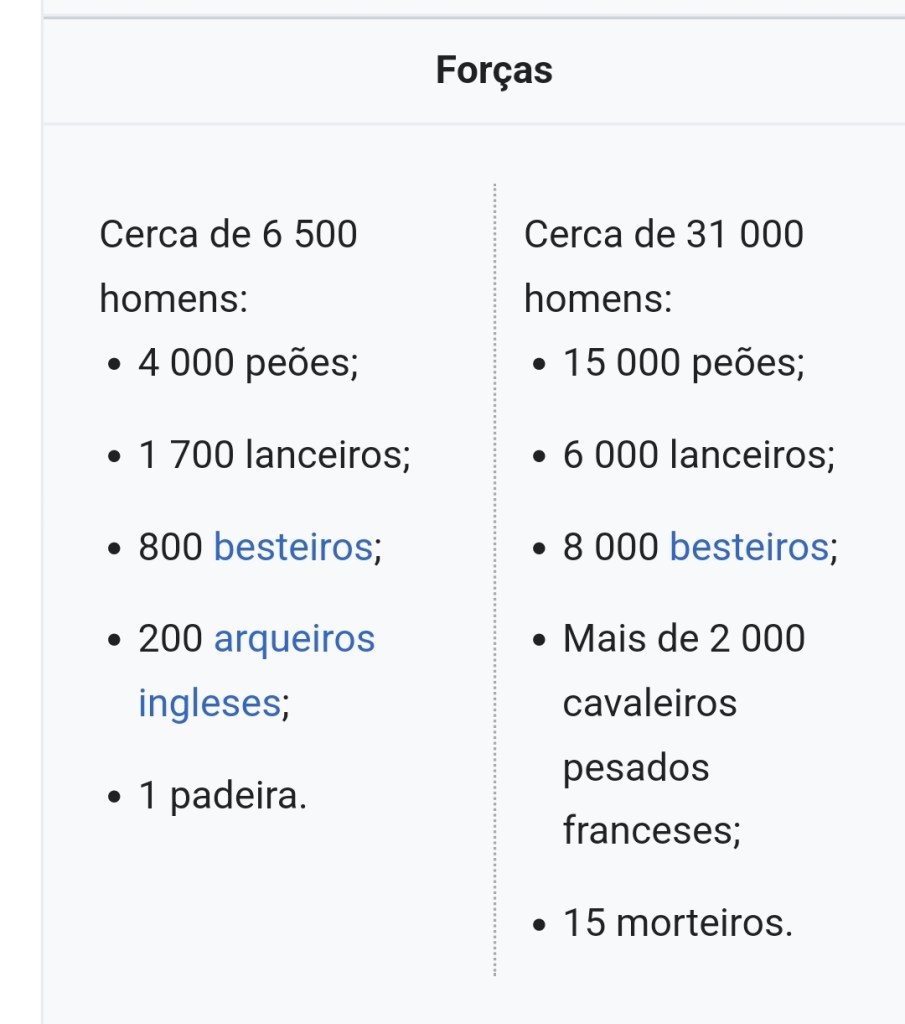

Este livro ficou para ler após a unidade curricular sobre a padeira de Aljubarrota, e já acabo de ler. É interessante por várias razões. A ortografia é muito diferente do que a de hoje (veja por exemplo o texto de ontem!) mas também vemos como a história é contada, realçando os aspectos que o contador quer reforçar na mente do leitor. Especificamente, nesta versão El-Rei Dom João I e o seu Condestável, Nuno Álvares Pereira vão visitar a padeira antes da batalha e ela fala muito da sua raiva contra os espanhóis que ousam pisar o chão bendito da sua terra, e declara a sua lealdade ao trono português. Evidentemente a ditadura queria educar os seus cidadãos nesta espécie dE patriotismo (apesar de Portugal já ser República!) Também omite o pormenor mais assustador da história: quando a padeira cozinha os espanhóis no forno com o pão de chouriço. Não me admira que não quisessem criar uma geração de filhos com imagens mentais tão horripilantes!

Ora bem, eu conheço os prejuízos do governo que lançou este livro, mas convém lembrar que todos os autores têm os seus próprios prejuízos, embora não sejam tão óbvios. É fácil imaginar uma versão deste história que enfatizar o papel da padeira como mulher independente e feminista, ou como representante do poder da classe operária, ou como empreendedora que queria defender o seu negócio contra uns criminosos, o seja ou que for. Sem perceber, absorvemos essas mensagens ao longo dos anos. Não é bom, não é mau, mas convém lembrar de vez em quando…

(if you’re interested in reading this book… Well, you can buy it, but it’s super-small and I have a copy that I downloaded and printed off the Internet. I can’t find the link, but it’s out there somewhere, so have a Google, you might save yourself a few quid)